My grandmother was a strong and compassionate Egyptian woman, a mother of three, and a pathologist. On a glass slide, exactly like the ones she used daily, cells from her colon biopsy were identified as undifferentiated, and within days she was diagnosed with Stage IV Colon Cancer.

Although I am learning how to care for people in sickness and health, someday, the chest compressions will be applied to my chest. Disease knows no discrimination, and death unites us all. Thousands of cancer diagnoses and precise and growing knowledge of cancer cell types did nothing to protect my grandmother from that which she knew so much about.

In Egypt, cancer is called ’the bad disease’, and bad it is. Over the next couple months, we watched as the bad disease took our beloved grandmother away from us. During that time, my family members, and my grandmother, had to make a series of challenging decisions that they were very obviously not prepared to make.

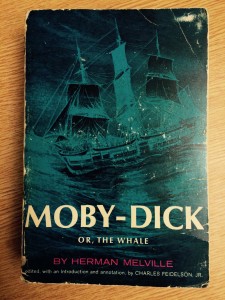

Medical advancements, although the main reason we are living longer lives, have caused the complexity and variety of end-of-life decisions to be ever increasing. Uneasy about the series of decisions that my family had to make and handicapped by my ignorance, I found myself reading Being Mortal by Atul Gawande. Atul Gawande led me through a vulnerable and imperfect but inspiring conversation about death and dying, exposing our medical system’s inability to understand health beyond the one-dimensional, and presumptuously noble, endeavor to prolong life at any cost.

While reading Being Mortal, I found myself enthusiastically nodding along, agreeing with the theme of the book: we need to change everything about our simple but destructive approach to aging and our increasing elderly population. Our singular approach to prolonging life simplifies complex social and medical decisions. It seems the attitude now is that longer life is all that matters. Ensuring nutrition and shelter is our only standard for a viable living environment for the elderly. We are failing our parents and grandparents.

Atul Gawande’s presentation of ideas changed how I perceive aging and our healthcare decisions at the end of life. I became a strong advocate of having conversations about the inevitability of our death and the choices we want to be made during our end-of-life care. I was convinced that society and healthcare should ensure that the elderly remain the authors of their own stories for as long as they are willing, and actively empower them to do so. Nutrition, shelter, and minimizing fall risk are minimums of care, not acceptable standards.

The Literature in Medicine Student Interest Group at my school decided to read Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal, and I could not be more excited. In the middle of our meeting discussing the book, as I was passionately sharing my ideas, it occurred to me that although I was full of strong opinions, I had done absolutely nothing to be a part of the solution. My grandfather had come to live with us after his wife of 55 years, my grandmother, passed away from colon cancer, and my only roles/concerns in his care have been to ensure food, sleep, and meds. My strong opinions had not inspired my actions.

Nodding along to Atul Gawande’s criticisms of our medical system is easy, but having an honest conversation with my grandfather about his priorities and end-of-life care preferences as he reaches 90 years of age is not so easy. How might I empower my grandfather to continue to be the author of his story? Believing that healthcare is a right and not a privilege is easy, but carrying out the responsibility that this belief invokes is not so easy. How might I work to help provide all my neighbors with equal access to high-quality care? Practicing the invaluable intervention of presence is not easy, and working day after day to hone my abilities at the art of empathy is not easy. How might I overcome my doubts, fears, and insecurities, and avoid being frozen into lack of compassion?

Too often my strong opinions do not inform my actions. Too often my hate for dysfunctional and unjust systems overshadows my love for the people in the systems. I call myself to love my neighbors more than hate the systems, for love is actionable and hate is stifling and tiresome. Let love fuel the tank, for compassion-based activism is the only kind that goes the distance.

Photo Credit: Dan Strange