Dr. Sugarman gives a speech rich with advice by sharing three life experience stories. These are very unique ethical situations that can serve to provide helpful guidance to freshly anointed doctors when they face similar dilemmas or challenges down the line.

In his first story, Dr. Sugarman discusses the 1993 revelation that the US government had supported a series of radiation studies on its citizens without consent during the Cold War era in order to determine possible after effects from potential nuclear fallout. Physicians and scientists helped conduct over 400 radiation experiments on unaware subjects. Dr. Sugarman served on President Clinton’s Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments to investigate wrongdoings and who may have been harmed. From this first story, he provides the following advice: “It is far too easy to be caught up in the rush to uncover the latest scientific truths. All of us, regardless of our professional careers, need to be alert to the interests of those who are subjected to science. Similarly, we all need to be vigilant regarding the temptations of big data due to the potential tradeoffs between enhanced knowledge and individual harms and wrongs, such as violating privacy. In addition, we need to be alert to what is driving the science that we do. Scientists and policy makers in particular must ask who is funding or supporting our work and for what purposes?”

In his second story, Dr. Sugarman speaks about his time on the Maryland Stem Cell Research Commission. There was a fellow commissioner named John Kellermann who was determined that stem cells were the solution to completely curing his Parkinson disease. This intense hope for a cure took priority over John’s personal, political, and ideological beliefs. Dr. Sugarman reminds graduating medical students “to not inflate the very natural hopes of people who are sick. An experimental approach that helps cure a mouse and be scientifically fascinating may never help cure a human…recognize the distinctions between treatment and cure. These differences matter. Anyone who is in anyway involved with the care of patients needs to be sensitive to them. Finally, the contemporary practice of delivering untested and unproven interventions that exploit this hope for cure are unethical and don’t in any way comport with the ethical obligations of beneficence inherent to the health professions.”

The final story that Dr. Sugarman shares is about his time serving abroad in Tanzania, which had widespread TB and HIV at the time. He also recounts a case when he suspected pericardial effusion in a patient. However, limited resources prevented diagnosis through imaging, and in the end, Dr. Sugarman performed a gutsy, blind pericardiocentesis that succeeded. “Working in Tanzania taught me many things that are of importance for your careers, regardless of whether you will be engaged with public health practice, a clinical role, or policy making. First, we respect one another by honoring appropriate cultural norms. For example, in the US we shake hands firmly and quickly; in Tanzania we hold hands gently and for long periods of time; in other cultures we kiss or bow or wai. Second, it is possible to engage patients in their care, even in desperate circumstances. Third, for clinicians, medicine is not only about knowledge but also about laboring. Aristotle considered medicine a techne, a skill or an art. And a skill needs to be practiced to be perfected.

…Please realize your degree is an invitation to learn. Stay alert for the lessons that will accompany your work. Welcome unlikely experiences. Welcome unlikely teachers. And welcome the ethical challenges in your work. Congratulations and all the best in the future.”

Read the full speech in the Commencement Archive: https://www.themspress.org/journal/index.php/commencement/article/view/340

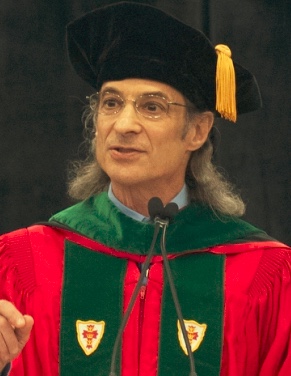

About Dr. Sugarman:

Jeremy Sugarman, MD, MPH, MA is the Harvey M. Meyerhoff Professor of Bioethics and Medicine, professor of medicine, professor of Health Policy and Management, and deputy director

for medicine of the Berman Institute of Bioethics at the Johns Hopkins University. He is an internationally recognized leader in the field of biomedical ethics with particular expertise in

applying empirical methods and evidence-based standards for evaluating and analyzing bioethical issues. His contributions to both medical ethics and policy include his work on the ethics of

informed consent, umbilical cord blood banking, stem cell research, international HIV prevention research, global health and research oversight.