“We can only give away to others what we have inside ourselves”-Wayne Dyer

Empathy is the ability to understand and experience life from another person’s perspective, which allows an individual to care for others in a genuine way. In medicine, it is arguably one of the most crucial qualities required to be a good doctor. Research shows that empathetic doctors are perceived as better caregivers, and are less likely to face malpractice suits. (1-4) In another study, which looked at how physicians’ empathy affected clinical outcomes for diabetic patients, it was found that the physicians perceived as more empathetic were more likely to have patients with blood sugars and cholesterol levels under control. (5)

Demonstration of caring and altruism during the medical school application process is almost essential for entry. However, several studies have shown that student empathy is negatively affected by medical education, particularly on entering the clinical years of training. (4, 6, 7) Various factors have been explored to explain this. The higher workload of the clinical years, exam pressures, as well as facing the realities of medicine on the wards (as opposed to previously idealised media images), could all be contributing to the phenomenon.

Moreover, medical students come from a background of overachievement, and stress and anxiety can result from not performing to the standards they expect of themselves. (4) Perhaps as medical students we have also learnt to put on a mask of compassion, kindness and emotional distance to protect ourselves from the realities of life; or maybe it is emotional blunting from just meeting too many ‘people with problems’. (7) Whether the reason for our rise in cynicism is attributed to one or all of these explanations, it seems apparent that the care and compassion we are able to show to patients is primarily associated with our own mental state. With a continuous backdrop of studying and time pressures, the stresses of all life events are heightened.

There has been a large amount of research into the stress, burnout rates and psychological consequences of medical school training. In one multicentre study at American medical schools, burnout was found to be common amongst medical students, and it increased by year of study. (8) The general consensus is that the medical school experience is challenging and demanding, requiring resilience and a balanced lifestyle.

Could medical schools provide more support to ensure students are well equipped to face a career filled with emotionally demanding situations, whilst maintaining the levels of empathy and emotional understanding crucial for strong doctor-patient relationships? All schools offer some level of student support, such as counselling sessions for those students that are experiencing mental difficulties or life challenges. Unfortunately, it has been shown that a clear stigma continues to exist against mental health and guidance in simple life matters. This has been described as “the hidden curriculum”, a culture that exists where doctors and students are led to believe that we are invincible and cannot become ill, either mentally or physically. (9) Often the first signs of vulnerability to mental health issues manifest at medical school, which actually leads to breakdown much later on. (10) Rather than allowing our future doctors to reach their breaking point before seeking help, we could build strong foundations and encourage introspection alongside academic learning. This would help our medical students and doctors truly reach their potential.

One avenue that has been explored to prevent ‘compassion fatigue’ and burnout is through the practice of mindfulness meditation. One study found that post-intervention levels of anxiety and depression were significantly reduced. (11) Mindfulness is currently taught at 14 medical schools and is continually gaining popularity. The University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry (USA) and Monash Medical School (Australia) are unique in that they have fully integrated mindfulness into their core curricula. (12) One study found statistically significant reductions in tension-anxiety in students on a mediation-based stress reduction (MBSR) program (from 14.5+/-7.2 pre-intervention to 12.4+/-7.0 post-intervention) in comparison to controls (11.3+/-6.3 pre-intervention to 13.4+/-6.9 post-intervention). (13)

What is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness is a process to become more conscious of the present moment in order to manage thoughts, feelings and strong emotions. (14) Although it was historically known as a Buddhist practice, with the aim to alleviate suffering and cultivate compassion, it can be practised without spiritual or religious affiliation. In the late 1970s, Jon Kabat-Zinn, a physician at the University of Massachusetts Medical Centre, developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), which takes away the esoteric aspects of the practice while retaining the core elements. This has gained considerable popularity, particularly in the field of pain relief. (15)

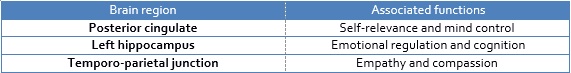

A study into the effects of meditation practice on the brain, conducted at Harvard School of Medicine, found that with meditation there was increased gray matter in the frontal cortex, an area associated with working memory and executive decision-making. There was also thickening of three key regions displayed in the table below. (16)

Furthermore, the amygdala, the area of the brain associated with the fight-or-flight response, and thus a key contributor to feelings of anxiety or stress, became smaller. (16) A second study by the same group found that practice for only 8 weeks appears to enhance regions of the brain associated with memory, sense of self, empathy and stress. (17)

Medical school and life as a doctor is a demanding career path. Thus, it can be argued that it is the responsibility of medical educators to both equip students with the academic knowledge required and the emotional intelligence to handle the day-to-day challenges. Mindfulness offers a method to teach medical students how to practically handle stressful emotions and situations, which helps them to become more centred, caring and empathetic. We can only give as much as we have, so it seems intuitive that students who are happier and mentally strong will provide better patient care. The evidence for mindfulness practice is very encouraging and it is interesting to see that two medical schools have already incorporated these practices into their curriculum.

Will mindfulness become as core to the medical school curriculum as the study of anatomy? If we value the mind as much as we do our bodies, then maybe it should.

- 1. Halpern J. What is clinical empathy? Journal of general internal medicine. 2003;18(8):670-4.

- Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. Jama. 1997;277(7):553-9.

- Brownell AKW, Côté L. Senior residents’ views on the meaning of professionalism and how they learn about it. Academic Medicine. 2001;76(7):734-7.

- Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O’Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Academic Medicine. 2008;83(3):244-9.

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Academic Medicine. 2011;86(3):359-64.

- Ren GSG, Min JTY, Ping YS, Shing LS, Win MTM, Chuan HS, et al. Complex and novel determinants of empathy change in medical students. Korean journal of medical education. 2016;28(1):67-78.

- Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Academic Medicine. 2009;84(9):1182-91.

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. Personal life events and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Academic Medicine. 2006;81(4):374-84.

- Sayburn A. Student BMJ: Why medical students’ mental health is a taboo subject. London: Student BMJ; 2016 [accessed 4 Apr]. Available from: http://student.bmj.com/student/view-article.html?id=sbmj.h722.

- Marshall EJ. Doctors’ health and fitness to practise: treating addicted doctors. Occupational medicine. 2008;58(5):334-40.

- Shapiro SL, Schwartz GE, Bonner G. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of behavioral medicine. 1998;21(6):581-99.

- Dobkin PL, Hutchinson TA. Teaching mindfulness in medical school: where are we now and where are we going? Medical education. 2013;47(8):768-79.

- Rosenzweig S, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, Brainard GC, Hojat M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction lowers psychological distress in medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2003 15(2): 88-92.

- Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. Jama. 2008;300(11):1350-2.

- Kabat‐Zinn J. Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical psychology: Science and practice. 2003;10(2):144-56.

- Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, Gray JR, Greve DN, Treadway MT, et al. Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport. 2005;16(17):1893.

- Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, et al. Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2011;191(1):36-43.

Featured image:

Meditation by Sebastien Wiertz