What is a stat laboratory? As far as most doctors are concerned, the stat lab is a mysterious place, located somewhere in the dungeon of the hospital, wherein a slew of unkempt “lab people” feverishly work to turn tubes of blood into useful numbers in the electronic medical system. While this view is not a complete misconception, I do think it would be constructive to provide a quick overview of how exactly these labs work, and how they fit into the overall healthcare picture.

There are two kinds of laboratories in the healthcare world: reference laboratories and stat laboratories. Reference laboratories perform high-volume, routine (non-time sensitive), specialized testing on samples sent from outpatient clinics and hospitals. These labs are generally located away from hospitals, in their own buildings, so they may have the extra space required to house highly specialized testing equipment and personnel. The downside to these labs is that the “turnaround time” for tests is slow (many hours to days), both because they are located offsite and because the specialized tests may take much longer to run. On the other hand, stat laboratories are smaller labs located on site in order to perform time sensitive (“stat”) tests. Although not very many highly specialized tests are available from these smaller labs, they provide all the basic testing necessary to support the emergency room and inpatient floors in a hospital, with turnaround times usually under an hour. Considering my work experience has been entirely at stat laboratories, I will focus on them in this article.

Stat labs have understandably become a staple in ERs and hospitals around the world because they quickly provide vital information about patients, allowing doctors to plan proper treatments in the short term. I mean, sure, you might be fairly certain that your patient has DIC, but wouldn’t it be nice to have a positive D-dimer to be sure?

First off, what is actually considered a laboratory, and how can you be sure the lab at your hospital isn’t churning out garbage? Well, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (the governing body for laboratories in the U.S.), the law requires:

“all facilities that perform even one test. . . on ‘materials derived from the human body for the purpose of providing information for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of any disease or impairment of, or the assessment of the health of, human beings’ to meet certain Federal requirements.”

I find it comforting that people (who are not me) dedicate their careers to quality control. Incorrect results lead to inappropriate treatment, which can have disastrous consequences on patient care. As such, each lab has its own quality control (QC) program in place, which includes running instrument calibrations/QC daily and monitoring the results over the short and long term. Much of the labor in the lab is dedicated to QC; in fact, depending on the test, the daily calibration and running of QC samples for one test can take the better part of an hour, and that’s if all the samples come into range as they are supposed to.

QC is the only way to be sure test results coming off the analyzer are accurate and precise. It is an unforgivable sin to release patient results when QC has failed, even when the other members of the healthcare team are adamant about getting the test results now. If QC has failed, all the results from that instrument are garbage until QC comes back in. Period.

Most stat laboratories are divided into roughly the following departments: hematology, urinalysis, chemistry, microbiology, blood bank, coagulation (PT/PTT), immunology, and specimen processing. In smaller labs, there are “float” lab techs who work in all of these departments. In larger labs, the techs are usually more specialized and stay in one department.

When, in this computerized day and age, an ER doctor puts an order for a blood test into the electronic medical system, the phlebotomist receives the draw order (if the nurse isn’t going to draw it). The draw order is usually a printed label, with the patient information, orders, and tube types listed on it. The tube type is very important; each colored tube contains specific additives tailored to certain tests (a CBC is run on a “purple top” tube with EDTA as the anticoagulant, etc.). Additionally, some tests require special handling (e.g. “on ice”) or can’t be opened until just before the test is run, as is the case for ionized Calcium.

The phlebotomist then goes to the ER, draws the blood, and transports it back to the lab. The specimen processor will then double-check to make sure all has been collected correctly, and mark in the system that the tubes have been received. At this point, the tubes diverge. The “red top” or “yellow top” tubes, which have no anticoagulant in them, must be set aside to be allowed to clot before being put into the centrifuge. The anticoagulated chemistry and coagulation tubes are thrown into the centrifuge and spun immediately to separate the RBCs, WBCs, and platelets from the plasma. The hematology tubes, which are also anticoagulated, are not spun, but put directly on the analyzer as whole blood.

After the proper tubes have been placed on the proper analyzers, most tests are automatically run and resulted. Exceptions to this include: a) chemistry results that are above the linear range of the instrument need to be diluted and re-run, b) blood slides that the hematology analyzer flags for tech review need to be looked at under the microscope, and c) the results that are critical values need to be called in. A critical value is the cutoff value at which the tech must call up to the patient’s nurse or doctor and report it. For example, the cutoff for a low potassium level may be <2.6 mEq/L at a particular lab, so if a potassium level of 2.4 comes off the machine, it cannot be resulted in the computer until the tech has verbally passed the information along to the direct caregiver. This is done because critical values are deemed dangerous enough that the doctor must know about it as soon as possible so as to treat it immediately.

After all the tests have been reported out, the tubes are taken off the analyzers and saved for a week in the refrigerator. This is necessary in case additional orders are added on later, or the patient dies and the medical examiner needs the blood, or to troubleshoot in the case of mislabeled specimens, etc.

And that’s the lab, at least the basics. Is it less mysterious now? I hope so.

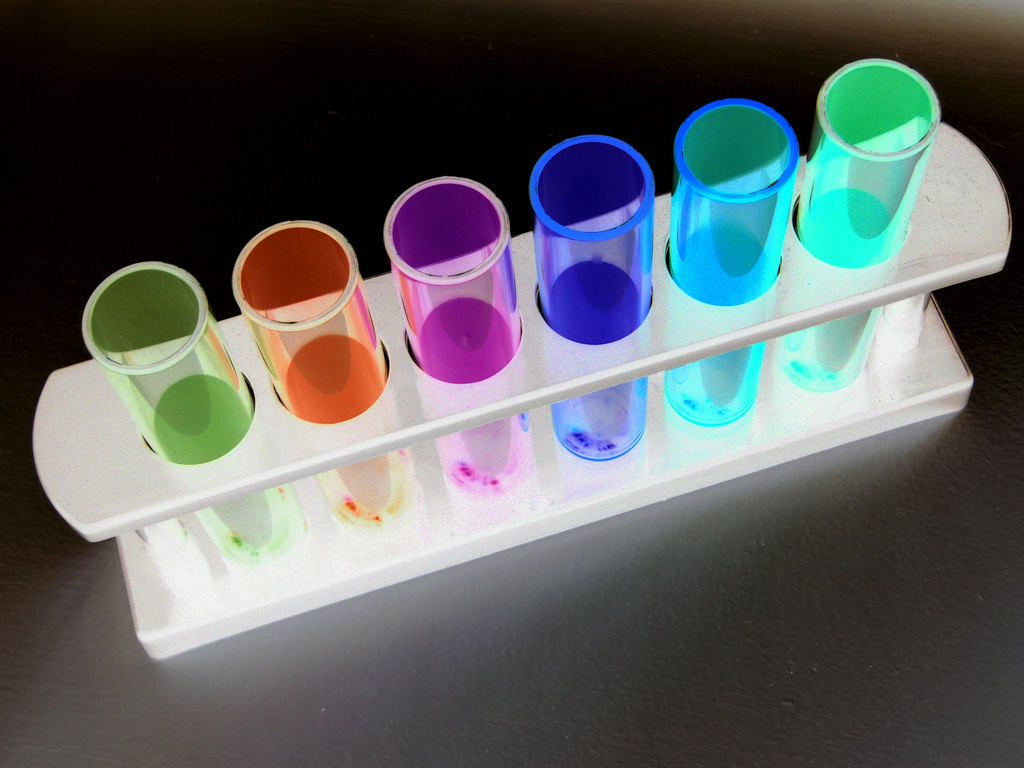

Featured image:

The Chemistry Of Inversion by Raymond Bryson